The Shape of Drama: defining and using "pivot points"

- Andrew Tsao

- Jun 16, 2025

- 6 min read

Defining units of action: the elements of a scene.

Playwrights use acts and scenes as demarcations to frame units of dramatic action in a given text. Audiences experience these units as individual segments through blackouts, scenic element changes, transitional sequences that may include dimmed lighting and /or music cues and pauses in the action. All these techniques are concerned with acknowledging the playwright’s intention of framing certain dramatic events and punctuating the drama.

Playwrights tend to define “scenes” as units of action made up of characters in conflict that arrives at a dramatic event. A dramatic event can be defined as stageable moment in time and space where a fundamental, often permanent change in one or more of the characters relationships occurs as a result of conflict or new information presented.

If a scene is a unit of action that contains a specific at a dramatic event, we can then further define that dramatic event as a “pivot point.” It becomes the defacto reason for the scene’s existence and is the result of the included action and the conflict depicted.

Visualizing pivot points across the entire drama charts the changes in relationships and circumstances that form the unique shape of a given dramatic work.

The requisite elements that comprise a given scene can be described as:

1. A set of Given Circumstances – existing situations, relationships, environments, past experiences and current conditions in which a character enters the scene.

2. The character and their active “inner life,” which can be defined as the sum of their emotional state and their psychological condition as they enter the scene.

3. A logic chain of action – how the tactics used by the character support their action, which in turn supports their objective, which in turn supports their superobjective.

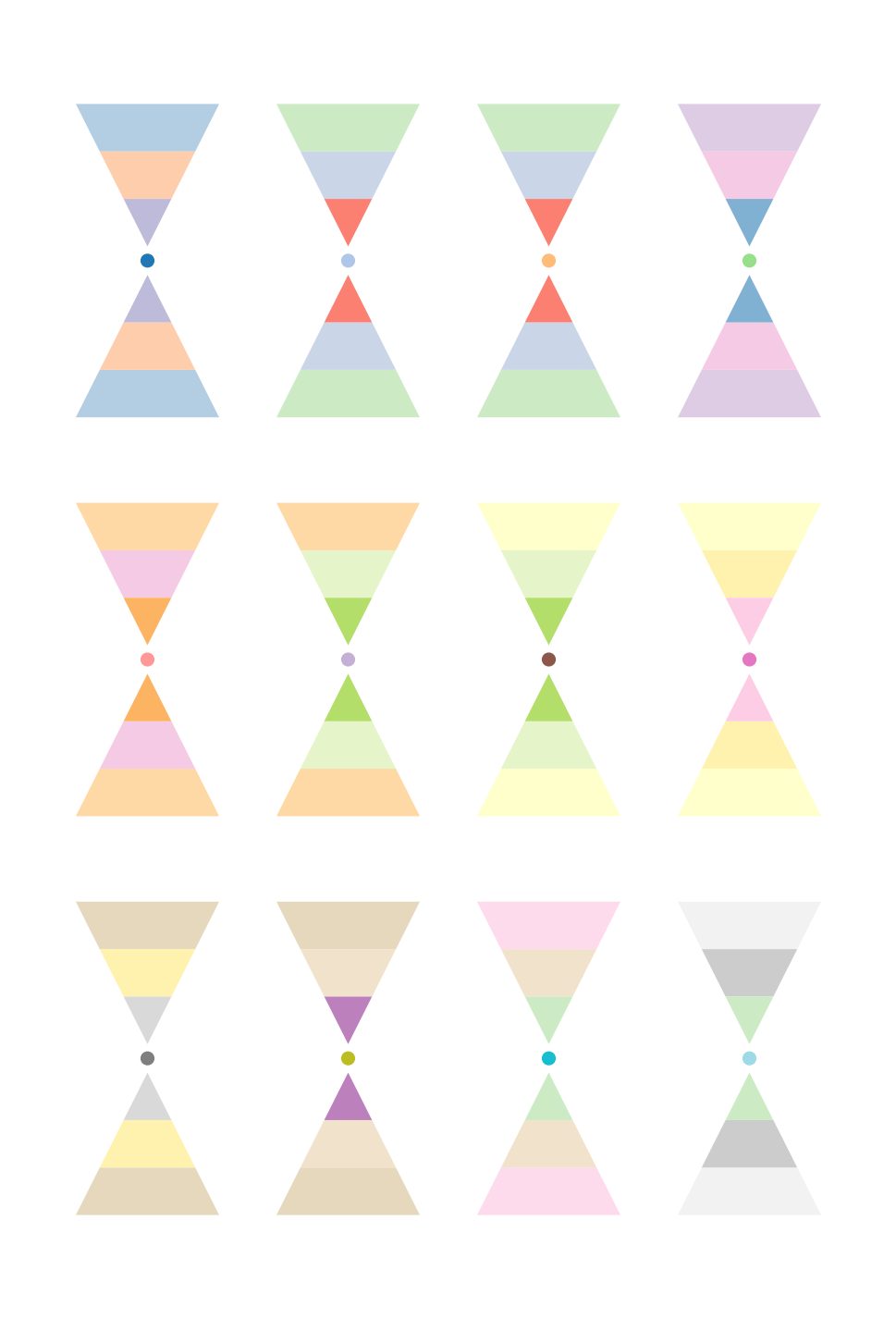

Figure 1. The form of a scene for a given character. (Tsao)

The tip of the scene, described here as the Logic chain of action is the sequence of “doings” or “tasks” undertaken by a character within it.

Figure 2. Inset illustration of the logic chain of action section of the scene pyramid. (Tsao)

Conflict arises when another character opposes this character’s “pyramid.”

Setting up opposing pyramids with a pivot point at the apex of the conflict results in this diagram.

Figure 3. Opposing pyramids, comprising basic elements of a scene. (Tsao)

Two or more characters in opposition create conflict within a given scene and the scene is a battle of tactical maneuvers until an event occurs, which ends the current scene and sets the stage for the next scene.

A dramatic event occurs when a character’s tactics either fail, succeed or reach a qualified stalemate with an antagonist’s tactics. This situation results in the change of circumstances for both or more characters.

Understanding this event, we can extract it from the diagram as a pivot point and position it in relation to other pivot points in the play, forming a landscape of pivot points that ultimately result in a unique shape.

The conditions that define a pivot point are:

1. A playable, stageable moment in time and space where the relationship between two or more characters changes fundamentally.

2. When a character’s action and tactical shifts cease due to conflict. This can be due to failure or the gaining of an advantage. (Usually near the end of the scene.)

3. When one or more characters make a discovery, comes to a realization, receives new information or otherwise experiences a fundamental change.

If the dramatic event is therefore defined and agreed upon after careful text analysis the initial rehearsal phase, then the actor, director and designer can all visualize from their respective viewpoints a particular moment in time when this event occurs and plan accordingly.

For the actor, understanding the event helps refine how the event can be played and can be a point of reference for tactical / action choices.

For the director, the event helps planning or framing the moment through staging, performance adjustments and stage picture / image so the audience perceives and understands its importance.

The designer can consider lighting, scenic and costume elements that speak to underscore or emphasize the event as well.

When used as a production / rehearsal planning tool, the following chart can assist the entire creative ensemble to work towards and unified and cohesive vocabulary that enhances the production overall. It becomes a means of creating another layer of punctuation in a dramatic work.

Figure 4. sample arrangement depicting individual pivot points through the course of a play. (Tsao)

The chart above shows an array of opposing pyramids, representing scenes or clear units of action. The varying colors indicate the unique nature of each scene: the given circumstances, character and their inner life, their logic chain of action may or may not alter from scene to scene. (Usually, their superobjective will remain the same barring a complete alteration of the overall given circumstances of the play, i.e. the village they are trying to save is wiped away by an enemy and no longer exists.)

Each pivot point is also unique. The moments of change that define the pivot point also have their own nature and are the result of the numerous changes that occur in the construction of the pyramids in opposition that result in the given pivot point.

Extracting each pivot point and laying them out on a graph it is possible to understand the potential relationship of the various points in terms of their place in the given dramatic text.

Placing the pivot points on a graph where time is X and Y is a scale of fortune to misfortune; a shape emerges that creates reference points between the pivot points and their relationship to time.

The subjective scale of “High Good Fortune to Extreme Misfortune” is used here as a sample of one way to chart pivot points across the time of a given play.

It borrows from Aristotle’s study of tragedy in The Poetics and the idea of fortune as a scale of success or failure for a character. For Aristotle, fortune was a moving, rotational condition that was subject to constant turns, or “reversals.”

Reversal of the Situation is a change by which the action veers round to its opposite, subject always to our rule of prob-ability or necessity. (Aristotle, The Poetics, trans H. S. Butcher 1895, London Macmillan.)

There are a range of scales that can be used along the Y axis depending on the kind of relationship an actor, director or designer is attempting to visualize between the pivot points of a play.

Examples of Y axis scales:

Achievement of goals / Failure to achieve goals

Fulfillment / Disappointment

Happiness / Sadness

Victory / Defeat

Acceptance / Disappointment

Thriving / Suffering

This guide is most useful for a director who is seeking to remind themselves about the nature and placement of certain key moments in their production: perhaps one early pivot point mirrors another late in the play, from a staging, costume or lighting point of view. Using the chart, a director can share this information with their designers for clarity. An actor may want a simple reminder in a long and complex drama of where and how certain pivot points relate to each other as they work to build a consistent, repeatable performance. A designer may wish to echo or expand on certain scenic, lighting or costume elements based on how the actors and the director use the pivot points.

Finally, charting the pivot points allow for a specific agreement or common understanding of important dramatic events in a play, how they might be arrived at, what they consist of and how they are related through the entire work, and their relationship / presentation in the production in real time.

The pivot point graph is not intended as a substitute for intuition, feel, subjective / personal experience or artistic choices. Any chart or guide can only be used effectively if it is taken in context, much like a coach may chart plays or statistics in a sports setting or a painter uses a color wheel as a reference guide. Whenever concrete or data informed elements are introduced into the creative process, caution and context are paramount. However, playwrights divide their work into acts, scenes or other concrete units of dramatic action in both calculated and intuitive ways. Therefore, using pivot points to identify structural elements already present in the text can be a useful tool.

Comments